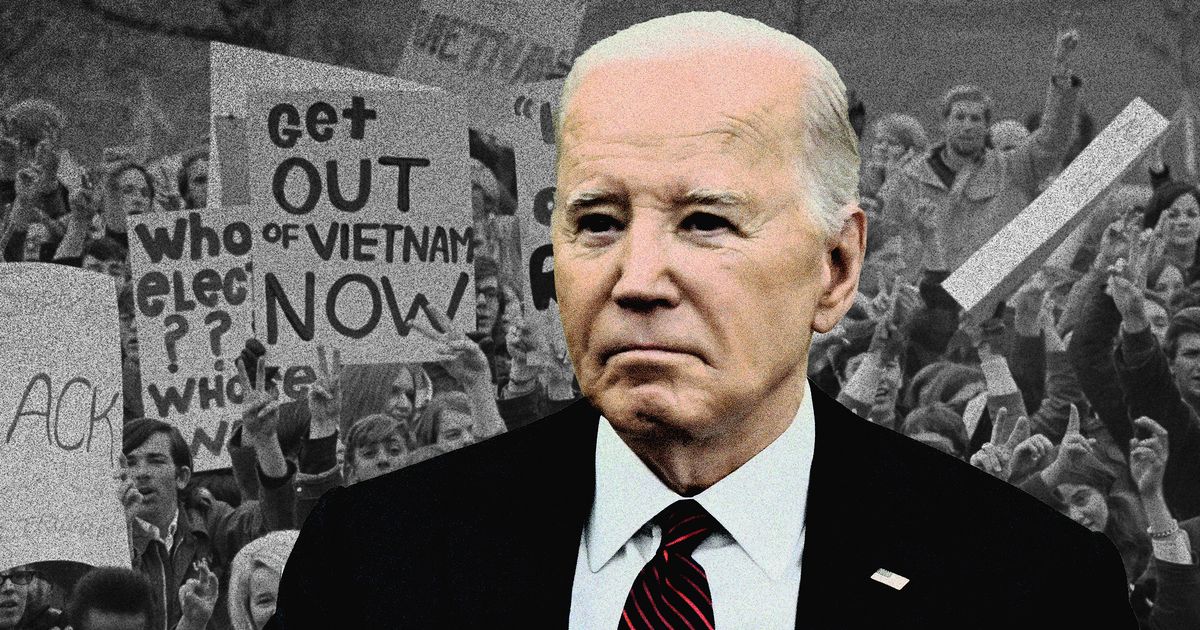

It's Not 1968 to Joe Biden

03/05/2024 11:01

For about a week, Joe Biden seemed confident that he'd said enough about the spreading campus protests against Israel's war in Gaza. He had mostly held back, occasionally condemning antisemitism at the demonstrations and the forcible takeover of buildings, like at Columbia. He'd also gone out of his way to add denunciations of "those who don't understand what's going on with the Palestinians" but sought to avoid getting sucked into the quickly widening political maw.

It took two days of violence on campuses on both coasts for the president to conclude he had to speak out more clearly. His message on Thursday morning was unambiguous: "We've all seen images, and they put to the test two fundamental American principles," Biden said from the White House. "The first is the right to free speech and for people to peacefully assemble and make their voices heard. The second is the rule of law. Both must be upheld." As he defended protesters' rights to share their views and deplored discrimination and bigotry against Jews, Muslims, Arab Americans, and Palestinian Americans, he zeroed in on the idea that "violent protest is not protected. Peaceful protest is. It's against the law when violence occurs." Speaking in the Roosevelt Room, he continued: "Destroying property is not peaceful protest. It's against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations — none of this is a peaceful protest."

Biden's reticence to weigh in aggressively early on had a lot to do with his primary focuses, which were far from any American campus: Trying to pressure Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu to scale back his assault on Gaza and to strike a ceasefire deal with Hamas that would secure the release of the remaining Israeli hostages.

But in his stance it was also impossible to miss a skepticism, shared by many of his allies, that young voters will actually abandon him en masse over Gaza. (Many of Biden's allies have recently noted the Harvard Youth Poll showing that young voters ranked the war 15th in importance out of 16 issues presented to them, far behind first-place inflation.) Even so, it is an article of faith among some prominent Democrats in his camp that a ceasefire could significantly ease the current pressure that he is feeling from young voters. His remarks showed that he has a greater long-term concern about civility and the perception of chaos — a line pushed by many of his Republican critics in the past week.

The protesters, many Bidenites conclude, are not representative of the broader youth population, and the encampments may fade away once summer vacation begins. They believe the dynamic is reminiscent of a familiar one for Biden: Young activists seeking to push him left ultimately siding with him over the unacceptable alternative presented by Trump's Republicans. When House Speaker Mike Johnson visited Columbia, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for one— no fan of Biden's Gaza policy — cheered students for booing Johnson but focused on an issue that unites Democrats, not the protests Johnson was there to talk about. ("Good," she posted, "he's trying to take all their reproductive rights away.")

The administration's restrained response also reflects its rejection of a common comparison of 2024 to 1968. Some around Biden have begun rolling their eyes at the frequent invocations of '68 in the press, arguing that while that tumultuous year — marked by campus protests, in some cases in the same buildings as this spring — is now used as a shorthand for chaos, actual similarities to the present are limited. (If there is any parallel to be drawn, some allies posit, it is to 2020. Plenty of Democratic leaders maintain that they would have won more widely then if not for some in the party embracing "Defund the police" amid that summer of protest.) Biden, who did not join the Vietnam War protests as a young lawyer, still remembers the political backlash to that year's demonstrations. He has talked on occasion about quitting his law firm to become a public defender in Wilmington when it was occupied by the National Guard following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s murder that year. Jill Biden, whom he married a few years later, had known one of the students shot at Kent State in 1970. By 1972, the Washington that greeted him upon his election to the Senate had transformed, jerked right by backlash to the antiwar and civil-rights movements and unrest in major cities as Richard Nixon's law-and-order campaign and administration dug in.

That's not to say everyone in Biden world is exactly confident about young voters on their left this time, particularly given all the polling that shows Biden performing relatively poorly with the group. For months, both Biden and Kamala Harris have been hosting smaller-than-typical campaign events for fear of disruptions — even their first big abortion-focused rally this year was interrupted repeatedly by pro-ceasefire demonstrators. There has been apprehension around the White House that Biden's coming convocation speech at Morehouse College could be peppered with protests, too. They are closely monitoring Columbia, where Doug Emhoff has spoken with leaders of the school's Jewish community about antisemitism. The university official in charge of the public affairs is a former Biden aide, and a number of its trustees have been in the Biden orbit, including private-equity investor Mark Gallogly, who worked under John Kerry in Biden's administration, former Obama Homeland Security secretary Jeh Johnson, and journalist Claire Shipman, the board co-chair who is married to Biden's former communications director Jay Carney.

Still, the tentative overall approach could also be a result of an emerging split in top Democratic ranks about just how worried Biden should be. The prevailing view is similar to the one summed up by John Della Volpe, the director of the Harvard poll and an adviser to Biden in 2020. "The top line to me is this issue is similar to climate: Among young people, for the candidates they would even consider voting for, there needs to be recognition and sympathy for innocent civilians, whether it's the 30-odd-thousand in Palestine or the kidnapped victims and other civilians in Israel. That is the most important thing," he said, suggesting that Biden was meeting this mark.

Others aren't so sure. Proponents of this view don't doubt the Harvard findings that Gaza is far from the top of most young voters' priorities list, but they worry that it is the animating concern for the specific young voters who are peeling away from Biden himself even as they say they support Democrats down-ballot. "This is kind of classic Biden land, where it's like, 'Don't worry, it'll all work itself out,'" says one senior Democrat who has known Biden for years. "A lot of times, it does! Except young people are really hard to get to and communicate with, and I'm not sure they really give a fuck right now" about Biden's pressure on Netanyahu. "The Biden way is just to dismiss it. I say dismiss it at your own peril."

In discussions with Biden allies, it's not uncommon to hear a final note of cautious optimism about even some of the protesters. Some are hopeful that a ceasefire could be reached before November, or even before this summer's convention in Chicago (where, in 1968, protesters clashed with police). Sentiment around the war could still shift. "It could change on a dot," says Della Volpe. "If a peace deal gets brokered, then Biden could enjoy a well-deserved bump." It wasn't a prediction, but you don't have to look back to 1968 to know how much can change in the final six months of an election.

In public, Biden has been unbudging even as he has made a point in recent weeks of meeting with critics of his Gaza approach, including a quiet sit-down in the Oval Office two weeks ago with Bernie Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez. (No one aligned with any of them will say a word about what was discussed, except that Biden heard them out. Before they met, Biden said of the congresswoman, "I learned a long time ago to listen to that lady.") Asked on Thursday as he left the lectern whether the protests had given him reason to rethink his policies on the war, Biden answered simply "no."